[ad_1]

• CJP calls for ‘cautious approach’ in matters involving constitutional bodies, office-holders; says verdict was ‘uncalled for’ after meeting between LHC CJ and ECP chief

• Justice Mandokhail says commission can only ask for one judge against a tribunal; primacy lies in high court chief justice’s final opinion

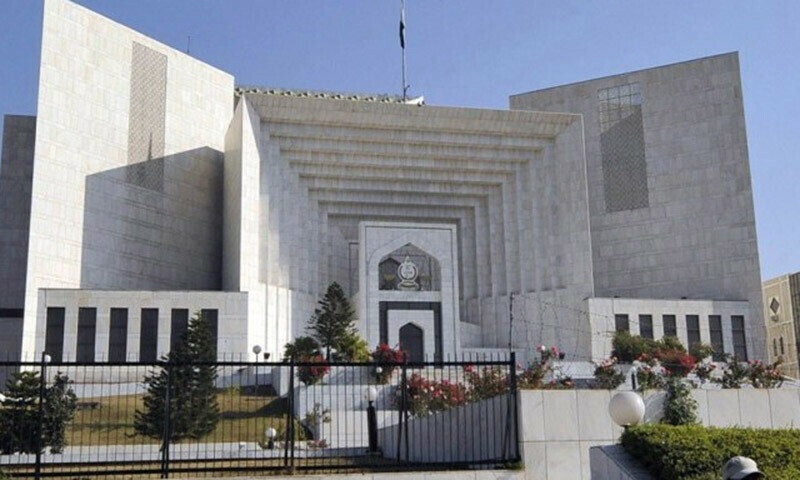

ISLAMABAD: As it set aside the order of the Lahore High Court (LHC) and a subsequent notification regarding election tribunals to hear poll-related complaints, the Supreme Court on Monday advocated a cautious approach in cases where a constitutional body or constitutional office-holder was party to a dispute, stressing that adjudication in such matters should be the last resort.

“The people, who we all eventually serve, expect nothing less,” observed Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP) Qazi Faez Isa. He was heading a five-judge SC bench hearing an appeal by the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) seeking a final determination on whether the commission or the LHC enjoyed primacy in the appointment of election tribunals.

Moved through senior counsel Sikandar Bashir Mohmand, the appeal before the Supreme Court had sought to overturn the LHC pronouncement.

At the last hearing on Sept 24, the apex court was told that four out of eight election tribunals had become functional in Punjab to settle election disputes, whereas the rest of the tribunals would be notified by the ECP. The judgement, however, set aside the LHC order, as well as the subsequent June 12, 2024 notification of appointing the tribunals.

The judgement said further adjudication was uncalled after the meeting between Chief Justice of the Lahore High Court Aalia Neelum and the ECP since the matter had been amicably resolved to the satisfaction of both.

Moreover, since such a dispute might one day have to be adjudicated upon, the court held that anything stated in the impugned judgement of the LHC should not be referred to before any court, the order said.

In his additional note, Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail observed that the ECP was a constitutional body and LHC judges were holding constitutional posts. “It is expected that members of both institutions must respect each other, and in case of any issue, they are supposed to have a meaningful consultation.”

In the case at hand, there was no meeting between the two institutions; therefore, there was no proper consultation, which resulted in litigation. During the pendency of these appeals, when the high court CJ and the ECP decided to have a meaningful consultation, consensus developed.

Justice Mandokhail observed that the Constitution and Section 140 of the Elections Act 2017 did not provide for any provision enabling the commission to request for a panel of judges for the purpose of appointment as tribunals. The intention of the legislature is evident from the fact that it did not assign power to the commission to ask for a panel of judges and pick and choose a judge of its own choice among them.

The commission must have faith in every judge and can only ask a judge against each tribunal, Justice Mandokhail observed, adding the primacy, therefore, lies in the final opinion of the high court CJ.

No doubt, the power to appoint tribunals rests only with the ECP, Justice Mandokhail observed, but in order to ensure a free and fair election, an independent machinery is necessary.

Therefore, the power to adjudicate such delicate tasks has been assigned to the judiciary, Justice Mandokhail, adding that in the case of appointing a sitting judge of a high court, consultation with the CJ of the high court concerned by the commission was a condition precedent.

The purpose of consultations is because of the realisation that the CJ is not only the administrative head of the high court but also in the best position to know and assess the suitability and availability of the judges.

Published in Dawn, October 1st, 2024

[ad_2]

Source link