[ad_1]

ARCHIVE: November 09, 2017

Pakistan’s ideological journey has reshaped the great poet philosopher Allama Muhammad Iqbal into a patron of its hardening worldview. Reviewing how he has been ‘reinterpreted’ into an ideological platitude is now hazardous because of his state-approved and clerically-backed identity as an orthodox thinker opposed to all modernist revision. At times, secular commentators longing for an identity rollback consign him to the category of ‘orthodox’ while praising Sir Syed Ahmad Khan as the true modernist. There is, however, steady evidence from his life that defies this orthodox labeling.

The climactic moment in Iqbal’s relationship with Pakistan came on December 25, 1986; some 48 years after his death. It happened during a national seminar presided over by General Ziaul Haq in Karachi on the birth anniversary of the founder of the state, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah. The topic of the seminar was, What is the Problem Number One of Pakistan? Present among the invitees was the son of Allama Iqbal, then a sitting judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan. In his speech on the occasion, Justice Javed explained why his father was opposed to Hudood (Quranic punishments) which Gen Zia had promulgated in Pakistan.

The controversial phrasing from the Sixth Lecture in Allama Iqbal’s book, The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, was: “The Shariat values (Ahkam) resulting from this application (e.g. rules relating to penalties for crimes) are in a sense specific to that people; and since their observance is not an end in itself they cannot be strictly enforced in the case of future generations.”

The reaction from Gen Zia was dismissive of Allama Iqbal rather than the Hudood he had imposed to appease his vast hinterland of clerical support. He had gotten into trouble with the clergy when his Federal Shariat Court decided that since stoning to death (Rijm) was not mentioned in the Quran it could not be a Hadd, that is, a punishment in the Penal Code. He had to change the Court to retain Rijm.

But Iqbal was prophetic: Pakistan has not stoned a single woman to death despite Rijm being on the statute book, nor has it been able to chop off hands for stealing. More literalist Iran gave up the ghastly practice of Rijm in 2014.

Pakistan is disturbed today by the continuing practice of bank interest after the Federal Shariat Court banned it in 1991 as Riba (usury) specifically mentioned in the Quran as also by Aristotle in his Nicomachian Ethic. Islamic banking which actually excludes the taking of Riba does so under a policy of complex self-confessed Heela (subterfuge).

In his publication Ilmul Iqtisad (1904), Iqbal’s first book in Urdu as an introduction to how a modern economy worked, he explained and clearly accepted bank interest as the lifeblood of commerce, knowing that it was considered banned by the clerics and accounted for so few Muslims in India’s commercial sector. He did so by accepting Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s view that “interest-banking was not the same as Riba/usury”.

HUDOOD AND IJTIHAD

Iqbal couldn’t have found approval in the Pakistan of today, much like Jinnah himself after he declared his preference for the Lockean state on August 11, 1947. To extend the argument, Iqbal was also opposed to the Fiqh (case law) favouring the Law of Evidence that discriminated against women and the non-Muslim citizens of the state. That he was unhappy with and scared of the traditionalist Ulema is testified by his arguments in the Lectures; there is also evidence that he inclined to a ‘liberal’ version of Islam in the new state.

Towards the end of his life he was collecting material to write on Fiqh and had been corresponding with the traditionalist Ulema to elucidate points that he presumably wanted discussed in his new work. He was not a trained scholar (Aalim) and was not accepted as such by the Ulema, but he thought himself qualified to produce a work of Ijtihad (reinterpretation). His son, the late Justice Javed Iqbal, wrote: “The Jinnah-Iqbal correspondence, discussing shariah, points to the establishment of a state based on Islam’s welfare legislation; it does not propose that in the new state any laws pertaining to cutting of the hands (for theft) and stoning to death (for fornication) would be enforced.”

According to Javed Iqbal’s biography of Allama Iqbal, Zindarood (1989), Allama Iqbal read his first thesis on Ijtihad in December 1924 at the Habibya Hall of Islamia College, Lahore. The reaction from the traditionalist Ulema was immediate: he was declared Kafir (non-believer) for the new thoughts expressed in the paper. Maulavi Abu Muhammad Didar Ali actually handed down a Fatwa (edict) of his apostasy. In a letter written to a friend, Iqbal opined that the Ulema had deserted the movement started by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and were now under the influence of the Khilafat Committee from which he (Iqbal) had resigned.

Allama Iqbal’s intent in reinterpreting Hudood becomes clear when he quotes Maulana Shibli Numani, who had written Seerat-un-Nabi, his renowned multi-volume biography of the Holy Prophet: “It is therefore a good method to pay regard to the habits of society while considering punishments so that the generations that come after the times of the Imam are not treated harshly.”

LIKE NO OTHER

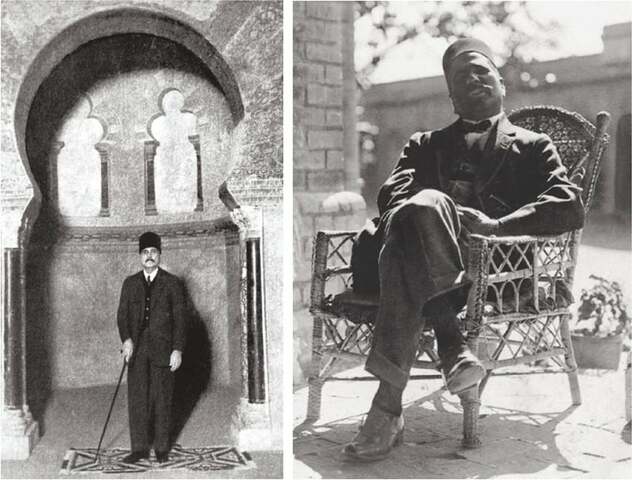

Allama Iqbal was a prodigy. In 1885, he stood first in grade one in Scotch Mission School, Sialkot, and began to be tutored in Persian and Arabic in a mosque. He was in class nine when as a teenager he started writing his juvenile poetry in Urdu. He passed matriculation in first division, winning a medal with scholarship. In his first year at Scotch Mission College, he started versifying under the pen-name of Iqbal and was published in literary journals.

He passed his BA exam in first division and won medals in Arabic and English. Three years later, though he passed his MA Philosophy in third division, he was the only one who passed and received the gold medal. He was appointed professor of Philosophy at the Government College, Lahore, chosen by Professor Thomas Arnold – the British orientalist who wrote a book proving that Islam was spread in the subcontinent not by the sword but by humanist preaching – who became his patron.

Iqbal was additionally appointed as the Macleod Arabic Reader at Oriental College, Lahore, on a monthly salary of 72 rupees and one anna. Later, he took time off from Oriental College to teach English at the Government College. His poems had started showing influence from Spinoza, Hegel, Goethe, Ghalib, Bedil, Emerson, Longfellow and Wordsworth.

He couldn’t disagree with Sir Syed Ahmad Khan whom he regarded as the Baruch Spinoza (d.1677) of Islam, rationalising and demystifying the scriptures. His job description at Oriental College included the teaching of Economics to the students of the Bachelor of Oriental Learning in Urdu, and translating into Urdu works from English and Arabic.

PIONEER OF SEPARATION

Lahore lionised Iqbal as the thinker poet of the city who could spellbind in a Mushaira while publishing erudite papers on such mystics as al-Jili whose concept of Insan al-Kamil was reborn in him with the help of Nietzsche and his ‘superman’ and ‘will to power’ but without Nietzsche’s rejection of morality – his “not goodness but strength” slogan. This was before he went to Europe (1905-08) doing his Master’s and Bar at Cambridge and his PhD with his thesis, ‘The Evolution of Metaphysics in Iran’ at the Munich University, becoming unbelievably proficient in German within three months.

The period 1908-25, back in Lahore, saw him produce some of his Urdu masterpieces while practicing law at the Lahore High Court. Reacting to Hindu revivalist movements, he journeyed from his pluralist view of India to a ‘preservative posture, advocating separate electorates and developing the first geographical map of ‘separation’ of the Muslim community in the northeast and the southeast within the subcontinent. All-India Muslim League courted him as the leading Muslim genius and listened to his ‘separatist’ thesis at its Allahabad session in 1930.

He contended that his idea of an autonomous Muslim state was not original but had been derived from the Arya Samaj Hindu revivalist vision of Lala Lajpat Rai of Punjab who first recommended ‘separating’ the Muslims. The view he put forward in his address remained pluralist which Pakistan neglected in 1949: “… [N] or should the Hindus fear that the creation of autonomous Muslim states will mean the introduction of a kind of religious rule in such states”.

As for Iqbal’s Nietzschean yearning for self-empowerment, Jinnah was made a practical example of it, as noted oddly by none other than Saadat Hasan Manto in one of his sketches.

Jinnah said this at the 1937 Lucknow session of the League: “It does not require political wisdom to realise that all safeguards and settlements would be a scrap of paper, unless they are backed up by power. Politics means power and not relying only on cries of justice or fair-play or goodwill.” It was this separate empowerment of Muslims in the face of such Hindu revivalist movements as Shuddhi (purification) and Sangathan (unification) that made Iqbal disagree with the Deobandi scholar Husain Ahmad Madani over the idea of India as a nation-state where Muslims and Hindus would live as one nation.

Like Lala Lajpat Rai, another Indian genius, Dr B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of India’s constitution, wanted Muslims to be given a separate state and wrote his book Thoughts on Pakistan (1941) which was welcomed by Jinnah who then asked everyone to read it to legitimise the League’s campaign for Pakistan.

ON THE SAME PAGE WITH JINNAH

Iqbal’s legally trained mind and his ability to write scholarly tracts quite apart from his ability to write the long poem or masnavi – abandoned by most poets of note after him – qualified him for all the three Round Table Conferences in London to present the case of the Muslims. His Allahabad address at the All-India Muslim League conference in 1930 was actually a learned survey of the nature of the modern state as imagined by such Western philosophers as Rousseau and could not have been comprehended by most Muslim Leaguers still basking in the afterglow of a doomed Khilafat Movement.

Noting that Pakistan’s non-Muslims observe the Independence Day of Pakistan three days earlier, Dawn editorialised on August 11, 2017, on how Pakistan first tried to suppress, then set aside, the August 11, 1947, message of the Quaid-i-Azam at the Constituent Assembly: “You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this state of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed. That has nothing to do with the business of the state.”

It is not only the founder of the state, Quaid-i- Azam Jinnah, that Pakistan has set aside; it is also the philosopher of the state, Allama Mohammad Iqbal, who has been rejected. Seventy years after its foundation, the state is malfunctioning and religion is a major cause of the shifting of its writ to the non-state actors. Denigrated are human rights – of the minorities and women – on the basis of a coercive interpretation of religion. So much so, that the faith-based but unexamined constitutional provisions in Articles 62/63 have finally destabilised governance by causing conflict between state institutions.

The writer is Consulting Editor at Newsweek Pakistan.

[ad_2]

Source link