The port city has witnessed 55 cases of lynching in the last three years, with experts attributing the trend to a lack of trust in police, courts and the justice system.

It was in the tumultuous decade of the 2000s that Karachi and I witnessed our first lynching. In the old city area of Nishtar Road, three street ‘robbers’ were apprehended, beaten and set ablaze by an enraged mob.

The incident unfolded on May 14, 2008, a Wednesday, when four men broke into an apartment, looted valuables and opened fire on the residents. As they fled, the family raised alarm, drawing the attention of neighbours. Subsequently, a chase began, ending only when the robbers were finally cornered by the crowd that had gathered by that time.

And then all hell broke loose. While one of the suspects managed to escape, the remaining three men were hit by any and everything available to the crowd — batons, iron rods, bricks, kicks and punches. They were dragged to the main road afterwards, where petrol was thrown at them and a matchstick was lit.

As the flames engulfed the robbers, police stood nearby and watched. So did the Edhi Foundation volunteers because the crowd didn’t allow them to rescue the men. It was not clear if the three men had died before they were set on fire or succumbed to it.

For me, it was difficult to comprehend what happened that day; an angry group of people played out all the roles of prosecution, jury, and judge on the street.

As a crime reporter in the metropolitan city of Karachi, I had grown acclimatised to gory blasts and bodies riddled with gunshot wounds, but lynching — where suspects were thrashed and torched in the name of justice — was an entirely new story to tell.

Little did I know that a decade down the line, such incidents would become routine, or so to say.

data compiled by the Citizen Police Liaison Committee, around 100 people lost their lives while resisting incidents of robbery in Karachi in 2024. It also highlighted a notable surge in the number of gangs involved in street crimes, with their numbers rising from 20-35 to 50-60.

With rising crime, lynchings have also increased in the city. As per the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), 55 suspects were lynched on the streets of Karachi in the past three years; 20 each in 2023 and 2024 and 15 in 2022.

“There are a number of factors behind the escalation of this so-called mob justice,” said Dr Zoha Waseem, assistant professor of criminology at the University of Warwick, England. “The lack of trust in the police, courts, and criminal justice system at large is partly the problem.”

One incident of lynching that remains fresh in my memory is the 2010 killing of two Sialkot brothers, which left the country shocked. Mughees, 17, and Muneed, 15, were lynched by a mob in broad daylight in Buttran Wali, in full view of police officers who made no attempts to stop the murders.

The brothers were declared robbers, their bodies were dragged through the streets and hanged against a water tank. The mob was about to set them on fire when the teenagers’ family members arrived at the spot and took them home.

It was perhaps one of the rare incidents of lynching where the seven persons accused of lynching were awarded a death sentence, six years to life in prison. The policemen present at the scene were sent to jail for three years.

The incident also prompted two students of a private university to conduct a study called ‘The Psychology Behind the Sialkot Tragedy’, which was published by an international journal in 2018.

Authored by Farheen Nasir and Khadeeja Naim, social sciences graduates from the Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology, the paper noted: “It seems, by and large, our society is becoming corrupt and evil and malice where people are losing self-control, feelings of empathy, trust on others and while enjoying others sufferings.”

It further highlighted that some of the most heinous actions and insidious behaviours can be attributed to the interplay of dynamics that question their morals, ignore their values and commit to performing acts they never would have thought themselves capable of.

The analysis showed that the common causes of human evil stem from deindividuation, inaction in the face of evil committed by others, propaganda to distinguish oneself from others, psychological distancing, rationalisation, semantic framing, and stereotypic labelling, which result in dehumanisation.

The research recommended that future avenues should include a focus on studies done on the nations where such gruesome acts of violence rarely happen to find out what social values they follow and the procedure to inculcate them in their nation.

nine dumpers and water tankers were torched by angry mobs near the main artillery leading to 4-K Chowrangi after a heavy vehicle hit and injured a motorist in North Karachi. They were angry over the rising traffic incidents in the city. According to the police, the mob also pelted stones at fire trucks when they tried to douse the fire.

Just two days later, another water tanker was set on fire in North Nazimabad. In a statement, the police said the driver had struck a motorcyclist near Paposh Nagar and fled the scene along with the vehicle. However, a group of 10-12 people chased and intercepted him near the Five Star Chowrangi. They attacked the driver and damaged the tanker’s windows before setting it ablaze.

Separately, last month, a robber was captured and beaten up after he shot dead a trader in the Quaidabad area. He suffered serious injuries and was taken to the Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre (JPMC), where doctors declared him dead on arrival.

In a similar incident in November last year, another suspected robber was beaten to death in Gulistan-i-Jauhar. In May, Orangi Town police rescued a suspected robber from being burnt alive by a mob.

badly beaten and set on fire by a mob in North Nazimabad. In the aftermath of the incident, then Sindh police chief Dr Shoaib Suddle admitted that people were convinced the system, which is supposed to provide justice to them, had never responded to their complaints.

In the following days, newspapers carried headlines such as “Karachi mob justice worries govt”, “Law of the jungle?” and so on. Clearly, it was a situation never seen before.

“Each such incident stands as a stark indictment of the justice system and should serve as a wakeup call for policymakers, legal professionals, political and social leaders, and civil society activists,” observed Abdul Khaliq Shaikh, former inspector general of Balochistan, who spent most of his service in Sindh and Karachi.

“Urgent reforms are needed to restore public confidence in the legal process and to cultivate a culture of tolerance and respect for the law,” the senior officer added.

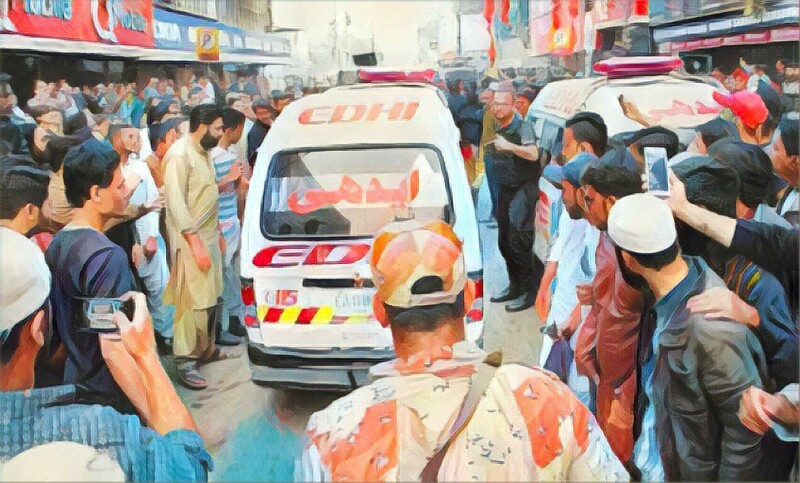

Header image: Security personnel and shopkeepers gather in the electronics market area of Saddar after a lynching incident. — PPI